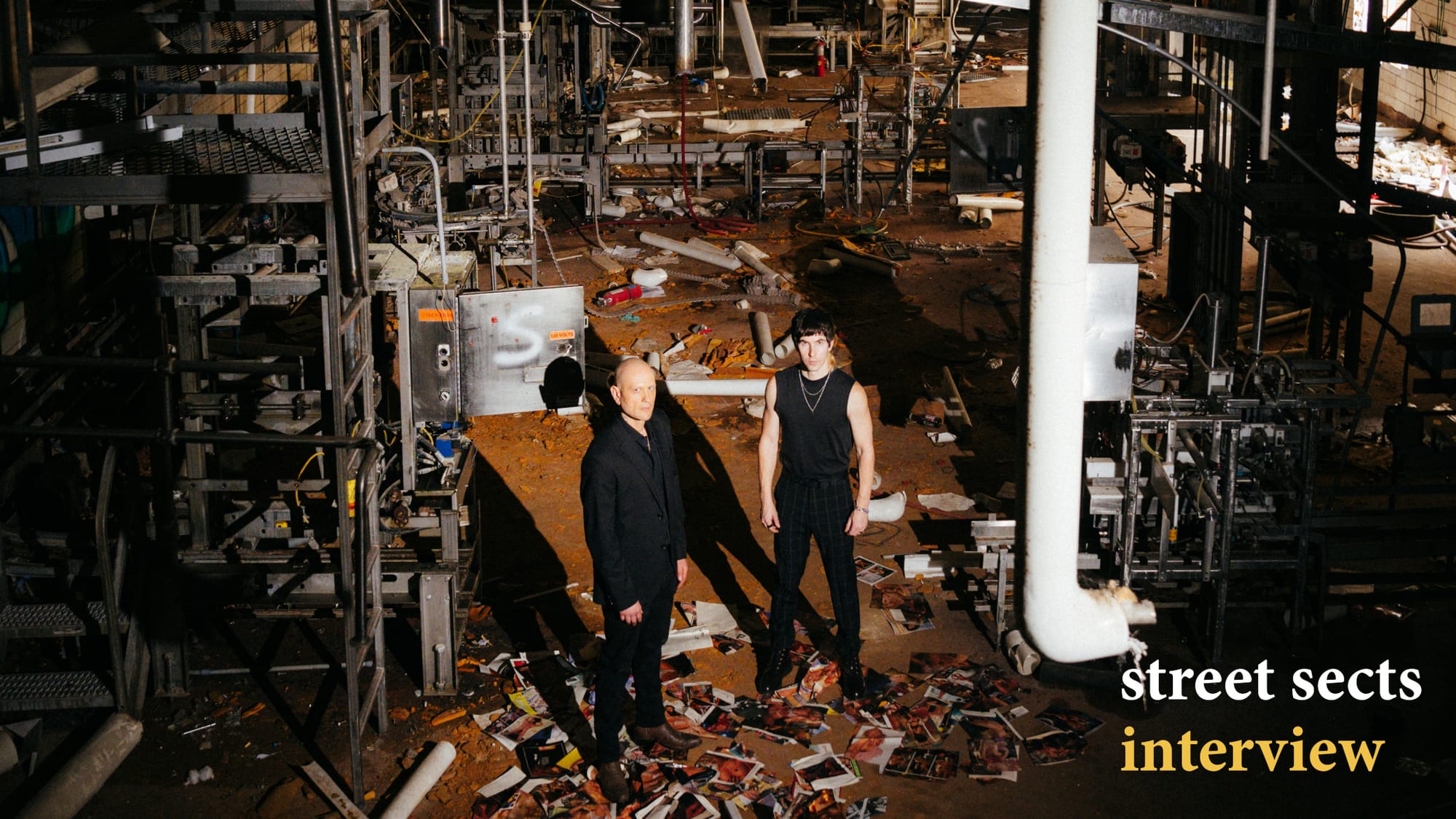

Inter/Sect: An Interview with Street Sects

The industrial duo talk returning from hiatus with two very different records, pivoting to synthpop, their inspirations in noir and pulp, the perils of alternate album mixes, and their (failed) attempts to prank producer Ben Chisholm

For as bleak and relentless as the music of Street Sects sounds, we can't seem to stay in that realm conversationally for too long. One look at the artwork or merch designs or even song titles from the industrial duo, and you can immediately get a vivid sense of the grimmest realms that band dwells within. But even when we dip into the darkest origins of that material, we keep pulling back to something that breaks through that cloud, without even intending to. In the last stretches of our interview, vocalist Leo Ashline has just finished detailing the frightening realities of his struggles with addiction and recovery that colored his writing of the group's long-awaited comeback Dry Drunk, and then it's mere minutes before he's talking about his love of pulp noir book covers, showing off a copy of Choke Hold by Christa Faust.

It's fitting that our conversation has this dichotomy, given the present nature of Street Sects. See, Dry Drunk—full of the band's characteristic noisy barrages, screams, industrial sounds, and pitch-black lyrical storytelling—is not the only record that Ashline and multi-instrumentalist Shaun Ringsmuth put out this past week. The two also dropped an entire second album, FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, under a new name—STREET SEX—and a markedly different sound, now inhabiting the world of neon-drenched synthpop, with nary a scream nor despairing scene to be found. But, as Ashline frequently notes in our call, "It's the same two people. It's the exact same two guys working on music with basically the same process, and the name is almost the same." Both even share the same producer, Ben Chisholm (perhaps best known for his longstanding work with Chelsea Wolfe). The shading and outlook may be different, but it stems from the same minds. All that shifts is the approach and perspective.

It marks the beginnings of a promising new chapter for the duo: formed out of Austin in 2013, the band mostly played in harsh, relentless realms for two LPs, an EP, and a serialized collection of thematically linked double-singles up through 2020. Then, Ashline relapsed back into addiction, and the two fell out of contact completely for a year and a half, putting the band on hiatus. But after Ashline's recovery, both musicians reconciled, and Street Sects has been more active than ever. They brought a long-awaited end to their Gentrification series of singles in 2o22, spent a run on tour with electro-industrial juggernauts HEALTH, and now are coming back with enough new music that it almost completely doubles the running time of their output. At the very least, both musicians seem more creatively invigorated than ever. ("We don't want to put it on the backburner," Ashline says toward the end of our conversation.)

I first came across Street Sects via their debut End Position in 2016, and immediately latched onto how seismic and gripping their whole world could be. From the moment "And I Became Ribbons" opens in an eruption of screams from Ashline and clattering cascades from Ringsmuth, I felt my heart race and my stomach in knots, and didn't find the feeling ever fading in the years since. The power of Street Sects, for me, has always been its capacity for total envelopment. Street Sects is a uncompromising band—not in luridness, but in an unyielding tonal command, never veering from their intent on fully plunging you into a every shade of darkness the human condition may yield. What's exciting about these latest records is that they both embody that promise, in ways familiar and unfamiliar to longtime listeners of the group. On Dry Drunk, there's the thrill of returning to old haunts to probe new depths; on FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, the pervasive morbidity is gone, but the full-throated commitment is still there, a shift in the shading while maintaining meticulous lucidity.

When I talk with Street Sects, they're just about to embark on a tour with Youth Code, King Yosef, and Insula Iscariot. Our talk begins with their storied live shows—a bombardment of strobes, fog, a silver wig, and, most infamously in the past, a chainsaw (sans the chain). Ringsmuth calls in from the band's practice space, still fine-tuning all the ways he'll be triggering tracks during the shows, and Ashline chats from his apartment. As they discuss the ways they've fine-tuned their approach to the live setting, it's clear that much has changed for the two of them since the early days of the project, but that intensity and immersion remains as crucial to them as ever. No matter where the conversation leads—whether on Street Sects or STREET SEX, field recordings or electronic production, or the glut of superfluous deluxe editions of albums crowding the digital and physical media market—Ashline and Ringsmuth remain musicians who take distinct consideration of the cumulative effect of their work, never short of deep thought on how even the smallest details may compound and bring their listeners into the world they create.

Below, read a sprawling interview with Leo Ashline and Shaun Ringsmuth of Street Sects, covering the challenges of putting out two disparate records at once, writing on the harrowing realities of addiction, embracing the pulp sensibilities of STREET SEX, their eclectic range of samples, and the band's (failed) attempts to prank producer Ben Chisholm with their music.

How has it been approaching the material for a live setting now? You've got quite a bit more to work from this time around than the last time you toured in 2022.

SHAUN RINGSMUTH: Well, in terms of the live material, it's kind of the same process, including anything new we're performing. We're going to have a balance with the fog. The fog was pretty essential to some of the early shows—the early early shows. But even with the last tour, we were able to get some of that, and it's mostly for interaction with the lights. It's to put a euphoric and confused feeling into the audience. We always went heavy, because that's when you really start tripping out. There may be some venues where we can do that this time around, but I'm not sure. We don't want to get in the way of the other bands and impact their performance, or have the show get shut down in any way. That's never a part of it.

LEO ASHLINE: As far as us rehearsing for this tour, it's been business as usual. As I'm sure happens with a lot of bands, there's a lot of stuff getting pushed to the last minute, which makes things stressful. But from my end, it's mostly making sure that I've gone out and done some preliminary damage to my voice so that the calluses or scabs or whatever it is that happens to a screamer's voice can build up a little bit before the tour, and I'm not going out there and blowing my voice out on Day 1. So that's been the majority of my preparation while Shaun is ironing out the kinks of the music production aspect of it.

I don't know if I've ever seen you play with the really heavy fog. The couple times I have seen you before, it's been playing with the intensity you can get from existing in total darkness and then flipping into an extreme flash of light, which is disorienting in its own right. It's all about making the most of whatever tools are at your disposal.

RINGSMUTH: Totally agree. It evolved over time. We got feedback from some people. Most people don't want to be immersed in lights and fog. If you're just casually going to a concert, or even if you know some of the bands, very often, you don't want that terror to float in. In some of our early shows playing the DIY tours in basements and people's houses, where we could really control the environment, I felt that too. There were times back there, where I'm so close to the lights that it's reflecting off stuff and getting me too. I'm leaning into the screen and keyboard, and it's anxiety-inducing. So I totally understood when I would talk to somebody about their experience and they'd say, "Hey, I saw you at this one house, and this person fell through a window." Which did happen in San Diego, unfortunately—someone was trying to escape, which is understandable.

Over time, it evolved a bit, especially when we first toured Europe, where we started to ask sound engineers and light people to engage with us a bit. Like, "Hey, after the first couple of tracks, we're going to use our own strobes to keep that feeling, and then say the third song opens in, and just go crazy with the lights and then do it intuitively after that." The feedback from people watching us was that they sometimes enjoyed it more, because they could see us. It lights up the stage more. If there's enough fog, no amount of various colors can cut through. It's fun to have a bit of both of that, and not just that one experience, especially for people who have seen us repeatedly. At some point, they maybe want to see the performers and see what's happening and get a sense of the humanity behind the music.

I think a flipside to this is talking about how you approach sound design, because what you do there with texture and atmosphere does so much in helping set the scene with any given songs of yours. How do you two engage with that, in your own art or others' art?

RINGSMUTH: I love that as a test. I love talking with someone who doesn't compose music when we're listening to something. Not as an annoying quiz, but just questions about what's happening in the music, because there's several hats to wear. Even as a composer, there's the listening experience, which you do need to try on, because you want to write a piece of music that's effective. I definitely enjoy noise music and sound design and instrumental music, but I always know when I'm listening to something where the composer got lost in it—where it's primarily for them, even if they were trying to write something that has a hook somewhere in it. It's interesting to listen with that in mind. Sometimes, I'm listening and asking, "How was that made?"

Especially with electronic music—for FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, I dove into bass music. I have a lot in common with a lot of the bass music artists. They're all using Ableton, they're really interested in the minor details of all the little squelches and bass sounds. We're talking like Au5 and G Jones and Tipper—music that I would never want to write, and if you had me listen to it ten years ago, I wouldn't have enjoyed it as much or gotten it. But other composers as well, people like Illangelo, who worked with The Weeknd. I could not stop listening to his State of Mind EP when I heard that—his immersive, emotive techno—and part of that is because of the sound design. That was somewhere very early on in the sketches of FULL COLOR ECLIPSE.

"I was only interested in freaking out into a computer and getting it out there with whatever sounds made sense."

I'd love to get more of a chronology of how these two records you're releasing came together, just to understand where each of these came about in the time since your last record. Was there any overlap in the creative process of these two? Or places where you felt your work on one spilling into the other? I'm mostly curious about how it came to be that these two records ended up being a simultaneous release.

RINGSMUTH: There's many components of that. In terms of the sound: to my surprise, yes, they did [overlap]. We were working on Dry Drunk somewhere in 2020. That comes off the inspiration from the earlier records. That's still looking at blending electronic with hardcore—bands like Portraits of Past or early Converge—trying to hear the emotive, metallic guitar sound and translating some of that into the music, and then adding sample-based stuff in there as well. That definitely ended up in Dry Drunk.

What surprised me writing the pop stuff is how much of [the process of Dry Drunk] was useful when I started writing FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, and how much I still needed to learn. As we were putting the final touches on Dry Drunk and finishing it up with Ben Chisholm, it informed how I heard that music, and all our previous music. But I had to level up the production value to write a different genre. I had never written pop music before. I'd never really tried to worry too much about the pre-mixing engineer mix. I was only interested in freaking out into a computer and getting it out there with whatever sounds made sense. Maybe I was making good choices, but once I started to really try to balance things out and make something that's impactful for any listener, then I realized that it was really connecting. Maybe because they're both electronic and [use the same] software.

There's a journey as to how those became a simultaneous... output... I was going to say "simultaneous release," but then I realized I would be quoting the Red Hot Chili Peppers. [Laughs]

I had that exact thought when I said that earlier... I was like, "Hmm... I don't like that."

RINGSMUTH: I'm not a fan, by the way. I'm not trying to sneak those in. [Laughs]

ASHLINE: Dry Drunk started with a lot of demos that Shaun put together pre-pandemic, before we took a brief hiatus. He had written probably thirty or so instrumental demos, and then we were out of contact for about a year and a half. During that time, I was working on vocal stuff for the demos. When we regrouped, right around the time the HEALTH collab came out and we toured with them, we started working on that stuff again. That's when we brought Ben Chisholm in and he started helping with the mix.

It was probably around that time that the idea for doing FULL COLOR ECLIPSE and this second project came, because a lot of these demos and the original artistic intent of Dry Drunk had been sitting and festering in my mind—and probably Shaun's—for a while. I felt like we needed something a little fresh, a little new, to keep the creativity going. In the past, we've tried to blend certain types of melodic elements within projects like Rat Jacket and The Kicking Mule—more accessible elements to the songs that were more overt, rather than snuck in there the way they are in End Position. It made sense to have this other project to cleanly divide those two impulses. That way, we didn't have to risk watering down the original project with things that may not necessarily stay true to the idea of being heavy or brutal or non-stop. It was a little slow at first, but the beginnings of FULL COLOR ECLIPSE started to happen around the three-quarter point into Dry Drunk. They were happening simultaneously, but the overlap was a little toward the back end of Dry Drunk.

There's a definite evolution for how the melodic stuff here on Dry Drunk sounds compared to what you were doing on those late 2010s releases you mentioned. And then there's something like "THE BIG HEAT" at the end of FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, which tonally resembles the kind of subject matter you'd hear in a Street Sect song. It's interesting—you can definitely sense those moments of overlap, even though the projects are two distinct identities.

ASHLINE: It's a song-to-song basis. While the intention was to get as far away from that original Street Sects sound as possible with STREET SEX, at the same time, it's the same two people writing the songs. There are going to be recognizable elements from both Shaun's music and my vocals. With Street Sects—especially lyrically and vocally—there's not a completely monochromatic world, but it's pretty dark. It's pretty bleak. It's rooted in a lot of negative ideas and feelings. When we were getting to the point where we were almost a decade into the band, I was personally really ready for something other than sitting in that misery. That's the place where I have to put my head when I'm writing the lyrics and working on the music. I know it's different for Shaun, because it's more technical and not as concrete in words and imagery as it is for me. Sometimes, it's not necessarily the most exhilarating experience sitting down and replaying all of the worst shit that I have either in my past, in my mind, or in my imagination to try to come up with a piece of art. I definitely wanted another outlet than just that, because it started to feel like a bit of a cage artistically for me.

With FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, it allowed me to be able to have a little more fun. Those songs could be about anything. It doesn't have to be about the hell I went through, or the hell this character is going through. I can write a song about a great time I had at the shoe store last weekend... there are no songs like that on the record.

I was going to ask. [Laughs]

RINGSMUTH: [Laughs]

ASHLINE: But in my mind, that's what I'm thinking. I don't want to have to be locked into this cycle of misery. Also, just the idea of being able to work on more hooks and melodies... that's something that's in the original material, but it's not forward, it's not prominent. When you take the voice and put it a little more front-and-center, and you have these more pop-styled song structures, it puts a lot more pressure on me as a singer to come up with melodies and hooks—to write in a different way. It's a lot more challenging. I can't just be like, "This part's crazy, so I'm just going to scream." Sometimes that's the easiest thing to do, because there's not a whole lot of nuance sometimes to scream in something. So when you're doing purely melodic singing, it's a lot more work, you have to spend way more time with the song. Because if you come up with a bad melody or bad words, it's going to be very plain and very obvious. So you've really got to take your time. And, personally, I just love that type of writing. For me, it was a great escape from things we've done in Street Sects. And it also allows a reset period, so that when we finished [FULL COLOR ECLIPSE], I was totally ready to do more of the heavy stuff. It's kind of a palette cleanser in that respect.

RINGSMUTH: It's a funny dichotomy, because while it allowed you more fun, it did the complete opposite for me. [Laughs] Everything I tried out at the beginning for FULL COLOR ECLIPSE was terrible. I was like, "I need to fire up a thousand YouTube tutorials to get this up to standard." So it's interesting to hear that. It's a good thing, though.

ASHLINE: And it's not to say that every minute spent working on FULL COLOR ECLIPSE was fun. I mean, it was still work. But it was a different kind of challenge. There was a newer sense of excitement while working on that stuff, like, "This is different, so I've really got to bend my mind and my voice in different ways to make it work." I'm very proud of the record.

RINGSMUTH: It was always fun waiting on the demos to see what you would do. There were a lot of pieces that didn't make the record, and some of them were way... I'll call it sillier than the silliness that's already on there. Just hearing something new from Leo—a new expression on that type of music—was fun.

The experience I had listening to these two records was that I dove into them one after the other, without hearing any of the singles beforehand. And I was really struck by how transparent and direct Dry Drunk's lyricism was, even compared to what's been on previous Street Sects records. And then I put on FULL COLOR ECLIPSE right after and had those first lyrics ("go stick your phone up your ass / set the tone to vibrate") dramatically shift the tone instantly. It felt like a hard reset as a listening experience.

RINGSMUTH: I think we both got to hear it fresh again when we had the listening event here in Austin. We had Johnny [Famiglietti] from HEALTH fly out and he DJed it, and we had some other acts like another LA act called MVTANT play. As uncomfortable as it was—and a first-time experience for me—we listened to both albums in full, with some DJing in between, with everybody. So I got to hear, as you mentioned, what that feeling of the opening track could be. It's not often that we're putting on these records now that they're done, especially now that we're working on stuff for our live show.

ASHLINE: It was definitely the first time we've ever listened to our records in a room full of strangers. It wasn't as awkward as I thought it was going to be, mostly because you could tell that the majority of people were just doing their own thing and talking. It was a club environment. But if it had been a thing where everybody was sitting down in chairs and quietly, attentively listening, I would've had to leave. I would've been like, "I can't take this."

RINGSMUTH: I think Joe [Anger of MVTANT] and Johnny were laughing at me, because I was deeply uncomfortable. I was behind our merch table, just pacing, like, "This has got to be over soon. Is there anywhere I can walk off to?" And then, as the person who created [the music], now I'm revising it. Speaking to how you listen to music, now I'm listening to my own music like it's somebody else who wrote it and I'm like, "Maybe I can get back into Ableton and raise the bass on that." I'm literally having those thoughts as we're listening. It's a different experience, for sure.

I feel like that's just part of the creative experience—always feeling like you've got to let something go, but then thinking, "But if I had more time, or if I tweaked it now that I have this thought in mind..." But that's never true to how it actually is. You've just got to let it be after a certain point, unless you're talking about recontextualizing it for a performance setting.

RINGSMUTH: Sure. I think it's helpful that Leo and I have a collaboration, because if it were [solely] on me and if I were working on electronic music, it is endless. You could keep revising forever. It is good to put a collection of songs or whatever it may be that you're working on and go, "This was this time period. This is the time capsule. I'm going to close it off and release it, and I won't try to dig it back up."

ASHLINE: There's a lot of instances nowadays of major pop and hip-hop artists who will go back in and remix a song, even after it's up on Spotify. "I've got a new version of this song." Anything's possible these days.

RINGSMUTH: Put demo in the title, and go, "It was the demo!" [Laughs]

ASHLINE: Not to bring up somebody who's obviously completely gone off the rails in a horrible way, but wasn't that basically what Kanye was doing for his last few albums? He was hosting these listening events, and then he was going back and remixing the records after he saw how people reacted to it. And then he was remixing the records multiple times after they came out.

Yeah, he's been doing that for almost a decade now.

ASHLINE: I don't know how fans feel about that. It's got to be exhausting for a hardcore fan to be like, "Now I've got to listen to Mix #7 of this record I've already listened to five times." I guess, for an artist, it's satisfying to be able to go back in and make those adjustments.

RINGSMUTH: My thought is that... as a listener, once you've emotionally connected with a record that's been out for a while and hasn't been edited in any way, that is the record. We were talking once about that first Pearl Jam album [Ten]. Didn't you say that they had, twenty years later, put out an edit of it that was supposed to be the "original intention"? Like, a punk version of it? But nobody liked it.

ASHLINE: It was a full-on remix, not a remaster. They thought the original version had too much reverb on it and gave it too much of a spaced-out classic rock sound. Then, twenty years later, they did the full-on remix where they made the instruments a lot more dry, a lot more present in the mix. And nobody wanted to hear it. Maybe they did. Maybe they were happy with it. But that's not the version of the album anybody's going to listen to when they go to listen to that album. It's kind of a self-indulgent thing, but artists can do what they want, you know, to make themselves happy. But it's exactly what you're saying. If the fans have already connected to a piece of art in a certain way... an alternate version of a song, like an acoustic version of a hard rock song, is one thing, but to completely remix something that already exists can be tough.

I feel like, unless you have a legitimate reason to go back and emotionally engage with old material, it will always feel like a fraught endeavor. Over time, you're inevitably going to gravitate toward different sounds, or feel like different things sound like "the right way" to approach material. But the truest thing is to just leave things as an encapsulation of where you were in that particular moment of creation. Things like those remixes are always strange to me because, even if it is closer to "how it should have sounded," the way you're engaging with it at a later point in time isn't necessarily how you would've thought about it in the past.

RINGSMUTH: I've even started to dislike reissues with like thirty extra tracks added. Maybe it's the way I grew up, having only so many records at one time. But say it's Elvis Costello's early albums—he rereleased them through Rhino Records and did liner notes, which is amazing, because he's an incredible writer. But then it would have a second disc full of outtakes and B-sides and alternate versions of the songs. And while I might have listened to those here and there, it doesn't change that first experience of putting the headphones on, being in my parents' house, and listening to an album start to finish, as I did then. Maybe we're just haters now. [Laughs]

I feel like that's just been to be expected since I was a kid. I grew up in the CD age where those kinds of reissues and deluxe editions was expected as the norm for older records, given the technical freedoms that format provided. I remember being really excited about that kind of thing as a kid—being able to see the nitty gritty of the creative process, or being able to hear unreleased songs that could've made the record, or how certain songs evolved from demo form. But now I'll open up a streaming page for one of those records and see how many tracks are there, and I just instinctively sigh in frustration, and open up the Wikipedia page to figure out where the record ended in its original release.

ASHLINE: Yeah, minus the "deluxe."

RINGSMUTH: I hadn't thought of that. Now that we're engaging with music digitally, it makes that bonus material even less easy to skip entirely. Maybe having the physical copy was a bit of an anchor, if you were ever going to listen to those sketches on harmonica or however those bands were writing the original tracks. If I see an album uploaded with thirty extra tracks, I better be a major fan. I think some of my fandom is behind me, in terms of the classic artists I grew up on.

ASHLINE: The worst ones are when they tack on a bunch of live versions at the end.

Yes!

ASHLINE: You finish the record, and then you hear the crowd noise come in, and you hear the guitar line from the song you've already heard. I don't need to hear a shittier version of a song I just heard five minutes ago.

The worst is when it's the only option on streaming. [Pause] Now I'm just rattling around in my brain the hypothetical Street Sects harmonica demos that never were. [Laughs]

RINGSMUTH: Oh, it's coming. Y'all just wait. We're going to have a Patreon for the harmonica.

I was trying to think of what song on Dry Drunk is most well-suited to harmonica and I'm drawing a blank. [Laughs]

RINGSMUTH: [Laughs] If there is one, we're in trouble. Maybe one of the interludes.

Speaking of those interludes, I was really drawn to the interstitial material on Dry Drunk. They're so pronounced on this record, sometimes taking up almost a minute of a track. How did you approach those? What was the appeal in using those to help sequence the record?

RINGSMUTH: In terms of sequencing, we've always done that. It anchors the album experience, for those of us left who want to go all the way through. Those interludes for Dry Drunk are actually the last contributions I made for it—we'll call them the newer contributions. As Leo was mentioning earlier, sketches for the record started in 2020. When I was convinced to do this, I thought we were going to scrap and start over. Leo and I had taken a break, we came back together, and the sketches were enough to where there were songs and full instrumentation, but they really needed work. But we had started speaking with Ben, and the idea was to send over what I had and have him dig into the mixes and bring life out of them, if they needed it. He did that for a long period of time, and we got well into Full Color Eclipse before we started getting toward the end of Ben's work on Dry Drunk.

We wanted to have that cohesiveness, especially [akin to] End Position. We've been calling [Dry Drunk] the spiritual sequel to it, in some senses. We definitely wanted to immerse the listener. I'm proud of a lot of those [interstitials], because I've changed a lot since 2020, as anybody who creates or produces music with software has. Hopefully, you're always trying to learn something new. I definitely spent a lot of time, especially when Leo and I weren't talking, just trying to work on production skills—not necessarily writing anything, but just working on that aspect of it. I brought some of that into those [interstitials], in little ways that may not be obvious to others, because you're listening to it as a whole and not hearing [those elements] isolated. But I really enjoyed some of those, and I wanted to turn a couple of those into full tracks, and may someday.

ASHLINE: When I listened back to the album, the interludes are my favorite parts of the album, just because they're the most minimalist compositions. The Street Sects sound, by and large, has been pretty maximalist—pretty crammed in every corner of sound. I love that and that's the key ingredient of our sound, but it's nice—in the terms of a record where it's beating you over the head so constantly—to get to those interludes and being able to pick out each little thing. As a listener, those are the moments I enjoy the most. That may partly have something to do with me being sick of the sound of my own voice. Those are the parts where I can just listen to something I didn't have anything to do with. I didn't work on them at all, so maybe that's why I enjoy them. I feel removed enough from it to be able to just appreciate them as something separate from myself. Shaun created those things completely separately, and I think he did an amazing job on those.

RINGSMUTH: There's one interlude—I won't reveal where it is, but I think it'll be obvious when you hear it—that places me in the moment right away, because of the context. I was at work one day and going into a stairwell, and I was walking down a floor. I thought I was on all cement, but I hit a platform and it made this terrible squeaking sound, like a mattress. I went all the way down, and then I went, "Wait a minute... I'm going to go back up and get myself walking down with my iPhone." So you can hear me taking steps down, and then just jumping up and down on this one part of the stairwell. I think I went around and clanged a couple other things too, just because there were just so many other interesting things that had metal sounds in there. But that particular awful squeaky sound ended up making it into an interlude, and I wrote music on top of it. It's the only one that doesn't sound composed in a fictional world. When I hear that one, I go, "Oh, it was that terrible job in that hot stairwell." I wonder if anyone else has ever noticed that one step when they were in there. I'll certainly be the only one to put it onto an album.

I love moments like those, where you just find things in your everyday environment that make sounds you can't artificially mimic.

RINGSMUTH: I agree. That's why I always loved those early Microphones records like The Glow Pt. 2 and It Was Hot, We Stayed in the Water—that crazy panning, and the sounds of cabinet doors being shuttered and doors opening, all that "found sound" stuff. Same with the Books and their sampling, as well.

To your earlier point, you kind of did set an precedent of expanding interludes by using the instrumental at end of "The Rooms" as the music that also opens the record.

ASHLINE: That one was actually Ben's idea.

RINGSMUTH: I was about to credit him.

ASHLINE: It started as the outro to "The Rooms," and then he found a way to cut it and place it at the beginning of ["A List Of All Persons I Will Harm"]. We have to give him full credit to that one.

Oh cool! Shoutout to Ben!

We've dipped into this a bit, but I'm interested to hear about the tracks that dramatically pivot on Dry Drunk—stuff like "A List Of All Persons I Will Harm" or "Love Makes You Fat" or "Riding The Clock." I'd love to hear about what went into having those songs turn on a dime and go into entirely different territories partway through.

RINGSMUTH: I wrote ["A List Of All Persons I Will Harm"] in particular in three different sessions. We were piecing together what could work and what would not work, and I rewrote those three separate sessions into one track. And we didn't just stitch things together randomly. Like, for instance, when it cuts away and it's the acoustic guitar section, we wanted it to have some thread. It's a case of trying to bring together different ideas from totally different writing sessions, instead of just writing the song from start to finish, on at least a few of those tracks.

I think "Love Makes You Fat" was intact. That one, I went back and forth with Ben on a little bit, in terms of what I was adding. But that one had a bit of that wild almost Fantômas feel to me. It doesn't sound like that, but it brought to mind some of those Mike Patton projects where things just flip in a manic punk rock kind of way.

ASHLINE: Since the beginning of the project, we always wanted our music to have that kind of rollercoaster feel, particularly the parts of rollercoaster where you have that hard jerk. That's hopefully disorienting in an emotional way. You feel like you're locked into a certain kind of feeling, and then the rug gets pulled out from underneath you, and then you have this moment of sadness or bizarre discomfort that's not necessarily pure anger. When you listen to a lot of aggressive, heavy, hardcore music—which is where we obviously take a lot of influence from—if you just have anger and aggression as your primary ingredient, it loses a lot of edge. It loses its effectiveness when you're on Track 7. So you have to bring in other emotions and feelings. Oftentimes, the most effective way to do that is to surprise somebody, rather than going, "We just finished a heavy song; here's our ballad." Everybody knows that kind of album layout, so it's a lot more interesting and a lot more exciting artistically to try to do these things within their own pieces.

Now when it comes to writing the vocals, it can honestly be an extreme challenge, especially a song like "Love Makes You Fat." When you hear that song without vocals, there's just so many parts. I never sat down and counted them, but there's got to be at least twelve to fifteen different sections of musical parts. So what I try to do is have the vocal, as much as I possibly can, tie it all together to sound more cohesive emotionally. That one specifically was a real challenge. You have to go with those turns. You can't just sing the same way over every part—it's not going to work—but you also want there to be certain kinds of continuity between certain melodies and types of phrasings throughout the song that bring it full circle in a way, from the beginning to the end. It can be fun writing vocals to some of these labyrinthine structures.

RINGSMUTH: You kind of reminded me that we've always played around with that a bit—trying to do a quick switch—partly due to hardcore influence and partly due to wanting to step into a new emotion in a song. We did that on "In Defense of Resentment" and "Feigning Familiarity." Both of those have what try to be an emotive twist at the end: something more melodic, something more cathartic.

ASHLINE: The end of "Our Lesions" too.

Or even something like the end of "If This is What Passes for Living," which scales back the sonic intensity for something that plays with negative space more.

RINGSMUTH: Agreed.

"It's not necessarily the most exhilarating experience sitting down and replaying all of the worst shit that I have in my past or in my mind to try to come up with a piece of art."

We've only talked it briefly so far, but I want to double back to what Leo was saying about FULL COLOR ECLIPSE being a palette cleanser. Obviously, "Turn Blue" is about pushing through repression and stripping away the pessimism that comes in usual Street Sects stuff, but I'm curious to hear more about what the tonal freedoms of that record were like for you.

ASHLINE: I knew that one of the cornerstones of the record was going to be sex, to some degree, or at the very least, interpersonal relationships. That's something I've largely avoided in Street Sects: talking about romance or love life, or anything related to that. One: who needs another love song? And two: it just doesn't really fit in that world. So I wanted to explore some of those things because we all have experiences with other human beings that affect us on some level emotionally, romantic or otherwise. I wanted to draw from some of those places that I don't get to draw from in Street Sects.

Part of what I found while working on some of that stuff is that I write about romantic or interpersonal feelings much differently now in my 40s than I would have in my 20s. A lot of the naivete and starry-eyed views on romance are just not really there anymore. Honestly, I'm kind of glad. You can look at these things in a much more clinical light. The feelings are still there, but you're able to analyze your place in them and maybe step back and look at the perspectives of the people around you, or the different characters you're trying to funnel those feelings through.

There's stuff on the record that touches on the music industry, too. When I sit down to work on a song, before I ever write a single word, I've spent countless hours singing along to the demos that Shaun sends me. I'm driving around, singing along, humming along in my room, in the practice space, and then I'll record dummy vocals—just nonsense things. I really get those melodies locked in. The music tells me how I feel. The music is going to inform how I feel, and how I feel is going to hopefully come across in the way that I'm singing these melodies. And then, once I have that, the words have to match that feeling in those melodies. When I get to the point where I'm writing lyrics, rather than sitting down and going, "This record is about Dry Drunk Syndrome; this record is about belligerence and anger and resentment," it can be just, "What's on my mind today?" And sometimes, what was on my mind was freaking out about how we were going to release these records. That's how a song like "PERPETUITY" came out. I was getting frustrated with a lot of the machinations of how the music industry works these days—like pretty much everybody involved in the music industry is, I'm sure. But if that's on my mind, I'm not going to be like, "I'm not going to write about that, because it wouldn't fit on Dry Drunk." No, let me find a way to tell a story about how I'm feeling about this particular thing and explore that. It was a lot of fun to be able to do that, and liberating.

This brings to mind my own questions I had about how joining Compulsion Records for these releases came to be for you. My impression is that it spun out of your collaborations with HEALTH in recent years, but I'd love to hear more about how you ended up signing with them.

ASHLINE: It kind of happened really, really fast. The plan was to continue putting out the records with the Flenser, who we've had nothing but a great experience working with. Jonathan [Tuite] is still a great friend. But the wheels were turning really, really slowly as far as getting those things out there. As I'm sure you're aware, he's got a huge roster and a lot of bands, and a lot of things to schedule for his releases. Like I'm sure some of the other bands experience sometimes, you're ready to put a record out, but it may not come out for another year.

While we were in the waiting period, we managed to finish FULL COLOR ECLIPSE, and as these records came together concurrently, it became extremely important for us to release them together, as being able to say, "These two records kind of happened around the same time, they're two sides of the same coin, and we need to be able to present them in that way." We were almost able to convince the Flenser to be able to do that. But they got cold feet about it. It's a lot for a band that's been on hiatus for several years to come back out and put two albums out on the same day, especially in the music industry right now, where the attention spans are at zero. Trying to get people to focus on two projects, two albums, on the same day is a lot. So we totally understood, but Shaun and I had spent so much time working on this and talking about this idea of releasing both albums simultaneously that it was just a huge letdown. But we were still going to go ahead and put out Dry Drunk first with the Flenser, and then FULL COLOR ECLIPSE later, though we weren't super thrilled about it.

Over the last few years, John from HEALTH will reach out to me every now and then and ask me to do backup vocals for something they're working on. I did some stuff on a few songs on RAT WARS, and I've done some stuff on a few songs on their upcoming record—just doubling stuff for Jake, or stuff in the background, or screams here and there. So John and I are always in touch, on and off. We were talking about how we wanted to do the albums simultaneously and were bummed that we weren't going to be able to. And then, out of nowhere, he was like, "We might be able to help you." He told us that HEALTH had just gotten the rights back to their first couple albums and they were rereleasing them themselves, doing them under this record label they were starting. Three or four days later, he called me and said, "We can put out both your records at the same time. We can make this happen for you."

I talked to Shaun that same day and we both went, "Let's do it. When are we going to have the opportunity to do something like this again? When are we going two finished albums with two different band names that we can release on the same day? When is it ever going to line up like that again? And when else are we going to have friends of us, who are also artists, offer to help us with this? We can't say no." While it was extremely difficult to not go forward with the Flenser, it just seemed like everything was lining up. Literally within a week and a half of those conversations with John, the ball was rolling. The music was getting sent out to the pressing plant. It was fast. After a year-plus of stagnating and wondering when [both records would come out], just seeing that momentum happen so quickly and efficiently was a breath of fresh air.

"These characters I'm writing about in the songs, you can't walk a block down the street without running into ten people who have struggled with some kind of addiction or personal hell."

You bringing up the two different project names reminds me that I wanted to ask about the origins of STREET SEX. I came across a 2019 interview where you mentioned considering it as the original name for Street Sects way back when, so I'd love to hear what made it cling to you as a project name and why it made sense to use it now.

ASHLINE: When the project first began, it was right after I had gotten clean, after being an alcoholic and an addict for ten to fifteen years. A lot of the final years before I went to rehab were spent in heavy amounts of crack cocaine addiction. When you're involved in that sort of self-destructive behavior, there's an entirely different component, other than just getting high: it's the securing of the drugs, the going out on the streets and getting the drug. That's its own kind of adrenaline and thrill, because you're constantly putting yourself in danger.

When I got clean, you have all of these withdrawal symptoms—physical ones that you can get over through drying out and going to detox and rehab, which go away, but a lot of the mental and psychological stuff doesn't. You have cravings for drugs and these prior behaviors. A lot of what I would find myself withdrawing from mentally was that feeling of being in constant panic and danger, because that does become its own addiction. So I originally wanted the band—sound-wise and feeling-wise—to be a sort of musical methadone for that addiction to adrenaline. That original name of STREET SEX was supposed to encapsulate that feeling. When you're out there, you're trying to get drugs fifteen or twenty times a day, you're out on the streets all day and all night. You're in these terrible situations, oftentimes with terrible people or people like you who are so far gone that they're dangerous to be around. While that kind of feeling is not exactly sexual, there's such a strong attraction to it—once you've gotten used to it—that it almost is.

When I gave Shaun the original name STREET SEX, he was like, "I don't know, that's a little too on-the-nose, maybe a little too campy." Then I realized that, if it was spelled "Sects," it kind of sounds the same when you say it out loud. Instead of just being campy and on-the-nose, it creates more of a "we" mindset. Obviously, these feelings I had were not specific to me. Hundreds of thousands of people have experience the exact same thing. These characters I'm writing about in the songs, you can't walk a block down the street without running into ten people who have struggled with some kind of addiction or personal hell. So it made sense to put it into the Street Sects name.

By coming back to [STREET SEX] now with a pop project, in my mind, it's no longer attached to that original meaning. Now it's meant to be something a little more fun, a little more campy, a little more neon nightclub hedonism. It's still a little dark, but not what the original intent was—that's Street Sects now.

It's fascinating to hear that—the same reason that name didn't work for the band at first now became the reason it fits for the different tone of this entire separate project. To that end, what made you decide to keep a kind of visual continuity between the artwork of Street Sects and STREET SEX, with Lizzie still serving as the recurring figure in both projects?

ASHLINE: Initially, it was actually tempting to go a different way visually. Here's a new project, a new name... we could really do something totally different. We talked about photography, different types of graphic art styles—completely having a total reset on the visual thing. But ultimately, it really made a lot more sense to keep it within the world. It's the same two people. It's the exact same two guys working on music with basically the same process, and the name is almost the same. So it makes sense for the visual thing to not be completely different.

We've had this kind of graphic art, comic book style with all the records over the years, but it's all pretty dark, pretty nihilistic. There's humor in there—I'm sure you've seen some of our T-shirts. It's not all dead serious. But the humor is so dark that it's almost not funny. [Laughs] So now it's like, "What if we took Lizzie and the comic book world and we made it a little more obviously fun?" We couldn't do that with Street Sects. We couldn't have Lizzie dressed up, looking sexy, sitting on the hood of a car in Times Square with a lollipop in her hand on [the cover of a] Street Sects [record] and get away with it. It just wouldn't make any sense.

So I started looking online for other illustrators who had a similar pulp, graphic novel style to what we had done, but a bit more on the sexual, classic '50s pin-up stuff. The cover of a detective novel always had some woman standing in a certain pose, with her hair blowing in the wind, and the book would be called something like The Dark Gutter. It would be some horrible crime book, but the cover would always have some buxom woman. It was a pulp thing. We found this guy Alan [Clough], who goes by the name FlopsComics, and that was exactly his style. I loved it and reached out to him, and thankfully for us, he was all about working with us. He's been amazing to work with. He's really nailed everything he's done so far for this album.

I love those kinds of pulp covers. Anytime I'm in a comic store or used bookstore, I spend so much time flipping through all the cheap pulp paperbacks I find. The art can be so ridiculous, but there's something so alluring to them and how over-the-top they can be.

ASHLINE: Absolutely, yeah. It's just so fun.

RINGSMUTH: Leo, who was that author you showed me recently that has covers just like that? They're excellent covers.

ASHLINE: Oh, that wasn't a specific author—that's a publisher. It's Hard Case Crime. They do a lot of reprints of old noir books from the '50s and '60s that have gone out of print, and they also do books from newer authors who are writing in the noir tradition. They have a different illustrator do each cover, just like they did in the old days, where no matter what the book is about, it's going to have some sexy damsel in distress or femme fatale on the cover.

Not to shoehorn it in, but that falls right in line with a lot of the film noir sampling across the Street Sects discography at times.

ASHLINE: Definitely.

RINGSMUTH: That's our music collab, if we have one, in terms of how it gets written. Leo pulled all the movie samples for all of our records, and would send them over to me, and I would place them where needed or appropriate, emotionally or otherwise, in the music.

I think the only one I was able to place in this record is the one from The Chase in here—the dialogue snippet where there's an order of "two bourbons and water."

ASHLINE: Where they're talking about Ben? [Imitating the sample] "BEN!" [Laughs] We had fun with that one, because obviously there's...

Oh right, Ben was producing! [Laughs]

RINGSMUTH: The funny thing to me is that Ben didn't say anything! He had to place it in there after I gave it to him, and I was like, "We got Ben good this time!" And he didn't say anything. Come on. It was a softball.

It didn't even occur to me, so I can see how that happened. [Laughs]

ASHLINE: There's even one part, I won't give it away—

RINGSMUTH: Oh yeah! [Laughs]

ASHLINE: —on one particular song, where I actually drop his name in a little ad-lib. I didn't put it on the lyric sheet, but the evil-eared listener might be able to pick it out. Stuff like that is fun while you're working on the record.

RINGSMUTH: Did he respond to that at all, after you sent him the vocals? [Pause] He had to have! Come on!

ASHLINE: I think we talked about it a little bit and he was just like, "Huh..." I think he's probably like, "I don't know what's wrong with these fucking guys."

RINGSMUTH: He's been in a little room listening to stuff, the ear decay has set in, and he's now like, "Now we've got Leo's jokes."

The one movie sampled across all of Street Sects that caught me most off-guard when I actually heard it in context was The Borderlands (AKA Final Prayer). I remember watching that for the first time after spending years with End Position and going, "Hey, wait a minute!" every time I placed a sample from that movie.

ASHLINE: I liked that movie a lot! Did you like that movie?

I really liked that movie, yeah!

RINGSMUTH: I've yet to rewatch that after placing all those samples. That movie is still horrifying. I've been listening to some samples throughout End Position now, thinking about bringing things into the live show, and every time I hear some of that horrible "getting eaten alive" sound coming out of a PA system, it's so destructive and terrible. The sound of something being chewed on, saliva and the screams—

ASHLINE: The sounds of digestion. [Laughs]

It was a similar thing when I finally got around to watching M a few years back.

ASHLINE: Someone just recently pointed out that another industrial band used that same sample on one of their songs, and I had no idea. If we had known that back then, we wouldn't have used that sample [on End Position]. But maybe it's for the best that we didn't know that, because it does work really well at the end there.

Since you've been ready to release both these records for quite some time, and since Leo mentioned that working on STREET SEX was a kind of palette cleanser, do you have a sense of how the dichotomy you've created here may pull you going forward?

ASHLINE: By putting them in stark contrast with one another, we just want to do both sounds much better than we've done before. We can look at Dry Drunk and be like, "How do we take that universe to the next level and improve upon those aspects in every single way, from the music to the vocals to the melodies?" And the same thing with the pop stuff. That was our first attempt at writing synthpop or whatever you want to call it. We don't want to put it on the backburner and then come back to it later, because you lose a little bit of those skills that you just built up.

RINGSMUTH: On the surface for the pop stuff, maybe there's a bit more dance focus to it, but I don't want it to stop there. I think it can embrace other kinds of pop and dive into that, whether it's other kinds of instrumentation or what have you. I think we're not going to try to limit it in that regard. There's nothing specific in mind yet, but Leo and I have a long history of listening to different kinds of records. I'll probably always want some electronic element—I just love electronic music. But I think it could take on other textures as we keep going.

I think I have five or six new demos that were not included at all with FULL COLOR ECLIPSE. There's a lot of runoff from that. These records have been done, and I don't want to stop. I'm only stopping for this tour. [Laughs] The stress of putting things together for this tour is the only thing that stops me. I think about it when I wake up and when I go to bed. I've definitely put together some new material, and some of that is entering some interesting tones.

As it goes for the heavy stuff? I think that music will always have some element of melodic direction. I don't know that we ever want to go full-on noise assault, unless that's the purpose of a track. I feel like maybe we did that on "Victims of Nostalgia." [Laughs] Something that just races through you. But it's nice to have another lane. And if there's an idea that's really emotionally so far removed from the heavier project, we don't have to dilute that in any way.

ASHLINE: Yeah, with STREET SEX, the main goal of that project isn't necessarily to be electronic or synth or any of that kind of stuff. It's working on the best songs we can write in a more traditional set of choruses, verses, or more recognizable [structural] elements. That's really kind of the only umbrella that we have for that project. We just want to write the best traditional type of songs we possibly can, which then allows us to go to the heavy project and get as wild and unhinged as we possibly can.

Dry Drunk and FULL COLOR ECLIPSE are now out via Compulsion Records. Stream both records below, and view Street Sects' tour dates here.